‘Sweete April showers,

Doo spring Maie flowers’[1].

From the late 16th

century, Brits appear to have hoped that poor weather in the month of April

would give way to sunnier days come May, though it’s likely that the sentiment

was first expressed much earlier than that.[2] So

synonymous is the month of April with rainy weather that one Anglo-Norman

author it turned it into a verb, avriller,

with the express meaning of ‘to rain, be showery’!

Mon avril et ma violete, Moun pré de mai e ma florete [...] Et mes

rosiers quant il avrille Ma flor qui pur giel ne s’esmaie Ross ANTS 1880

[My April and my violets, My May meadow and my flower [...] And my

rosebushes when it rains, My flower which does not fear a frost]

|

| Image of a man holding flowers in April calendar BL Add 21114 fol. 2v |

There are no shortage

of Anglo-Norman terms to talk about inclement weather, which is perhaps unsurprising

in a language used in the British Isles!

The weather could be anuius

(‘cloudy’), pluius (‘rainy’) or cuitus (‘stormy’; though normally an

adjective meaning ‘hasty’). The Latin word for storm, tempestas [3],

gave rise to a host of terms in Anglo-Norman to refer to bad weather. One could

refer to inclemency as a destemprance (also

used in English in the form distemprance) or as an entempauns

or merely as a tempeste (which

persists in English as tempest and in French as tempête).

les maisons [...] abatuz par tempest de vent GAUNT1 ii 177

(the houses [...] knocked over by a wind storm)

So great was the rain

that one could simply use the word for river, flueve, to refer to the weather! The most frequently used terms for

rain though are those that continue to be found in Modern French: pluie and pleuvoir (pluvoir).

E l’eir par venz e par fluvies (var. par

pluie) commovera Antecrist 113

(And the air will be shaken by wind and rain)

Along with the rain, comes

the wind! Anglo-Norman had multiple terms for wind, beyond the general term vent. These terms refer to specific

types of winds, generally in reference to the direction from whence they came

and are frequently adapted from the names of the Latin gods of the wind. Thus

the wind called affricum (i.e. from

Africa) is one from the south-west, the wind called aquilon is from the north, after the god of the same name. An austre is from the south, derived from

the Latin wind god Auster, while a favonyn

is from the west. This last wind is derived from the Latin Favonius, which might be more familiar by its Greek name Zephyrus. This wind was believed to

bring the spring. (Favonian is also

used in English but was borrowed from Latin in the seventeenth

century.)

Atant lur vynt de le occident un vent favonyn Fouke ANTS 43.9

(Then a Favonian/westerly wind came to them

from the west)

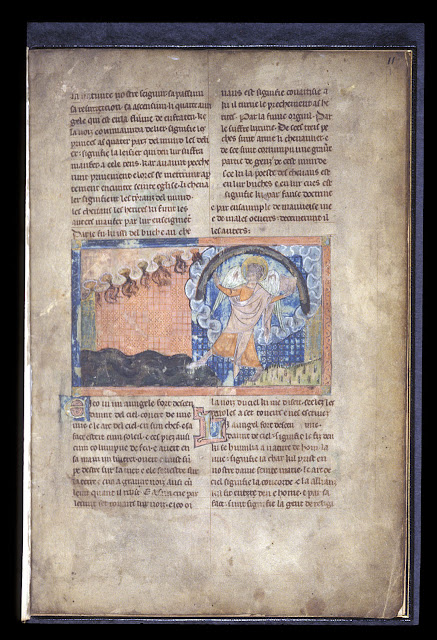

|

| Depiction of the winds BL Royal 20.D.1 f.281r |

Another wind, which is

the subject of a newly created entry in the AND, is called the plovel. Also known as the plougol, it derives from the Latin pluvialis, that is, relating to rain,

thus is it the word given to a wind from the south(or west) believed to bring

the aforementioned April showers.

The Latin term aura,

meaning ‘favourable wind’ later developed the sense of ‘weather conditions’.

This word is etymologically related to the Anglo-Norman terms of or meaning ‘a gentle breeze, soft

wind’, oré meaning either a

favourable or a violent wind, as well orage used as well to indicate a favourable wind or a violent wind storm.

After the wind and rain

comes a rainbow, known as an arc de ciel or

an arc en ciel (see arc 1) (literally a ‘bow of the sky’;

Modern French uses arc-en-ciel). The

phenomenon was also called iris,

after the Latin goddess who personified the rainbow.

Yrim l’arc del cel apelom Que nus contre pluie veum; Pur ço ad num

yris la pere Lapid 245.1281

(We call iris ‘rainbow’ which we

see against the rain; this is why we call the stone iris (a variety of quartz which displays the colours of

the rainbow))

|

| Rainbow BL Add. 38842 f.1r |

Hopefully as we get

closer to May we will see the weather begin to enbelir, that is, to become more beautiful and give way to clerseie (‘clear weather’). Perhaps

then we will see the ground asolailer (‘to

dry in the sun’) and enflurir (‘to

bring forth flowers’) and reflurir (‘to flourish anew’). Hopefully this spring

will also bring the editors, working on the revision of P, their first

attestation of the word printemps,

that is, ‘Spring’, as this form is currently absent from the dictionary![4]

[1] Thomass Tusser, Five hundred pointes of good husbandrie.

Eds. S.J.H. Herrtage and W. Payne. London: English Dialect Society, 1878, p.103.

[2] Chaucer began The Canterbury Tales invoking the

showery weather of April, ‘When that Aprill with his shoures soote...’. The

Riverside Chaucer traces the origins of this topos in Romance literature

and parallels in other works (Third Edition (1988), p. 799).

[3] We will

continue to give page reference for DMLBS headwords in the AND, the dictionary is

now available via www.logeion.uchicago.edu where is

is possible to search by headword.

[4]

Printens is attested from 1164

in Old French [DEAF prim (printens)] but no Anglo-Norman citation using the word has been found.

However, as it is attested in Middle English, under the form prime-temps from 1425, it

would suggest that the term was likely in use in England. There was another way

to refer to Spring in Anglo-Norman using the term ver. This term will be familiar to

speakers of Italian and Spanish, where primavera is used to denote the season.

Comments

Post a Comment